ICC chessclub.com

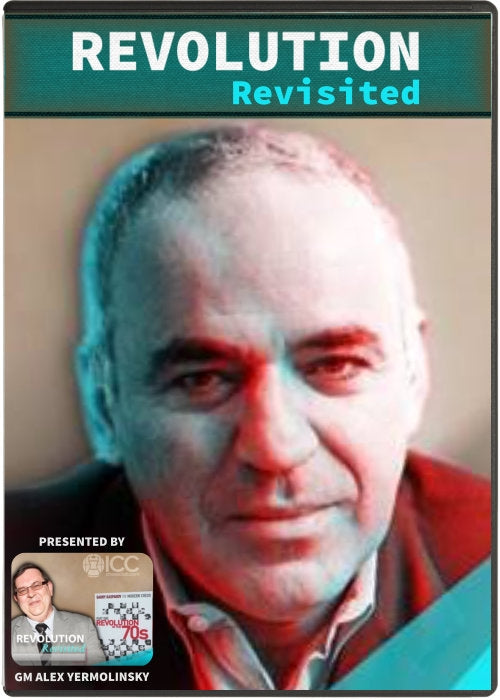

Garry Kasparov's Revolution Revisited - by GM Alex Yermolinsky

Garry Kasparov's Revolution Revisited - by GM Alex Yermolinsky

Couldn't load pickup availability

Garry Kasparov's “Revolution in the 70's” was published in 2007 as the first book of “On Modern Chess” series. Soon it was followed by three tomes on his matches with Karpov, and then Garry moved on with his critically acclaimed “My Great Predecessors” suite.

While all of the above are excellent works, “Revolution” has always been my favorite, because it's light on analysis and big on observations and conceptual thoughts. While this book deals with opening theory, it should not be taken as an all-inclusive manual, some of the sort of “Encyclopedia of Chess Openings According to Garry Kasparov” - should such title exist it would have been a book of 10,000 pages.

Instead, as the title suggests, Garry takes the reader on a journey through the free-thinking days of the 1970's when a new generation of players, born after WWII, set to work to extend the boundaries of existing theory.

The video series consists of 23 chapters, each being devoted to a particular opening line that was introduced in the 1970's or whereabouts when Garry himself was a good Soviet schoolboy, excitable and inspired.

Garry studied them all and built his opening repertoire on the mix of classical and modern.

Kasparov begins his chapters with introducing a stem game or two, followed by overview of current (circa 2005) developments. This is an essential method one should apply to studying openings: historical perspective before database search of recent games.

In my videos I try to follow through on the directions set by Kasparov, to see how the ideas he mentioned stood the test of time in the ten years that passed since his book came out.

Part 1 The Hedgehog system

The Hedgehog is more than a line of the English Opening, it's a concept that can be applied to many openings, from the Sicilian to the King's Indian Defense. Black eschews the traditional central pawn placement in favor of the fire-retarding elastic “small” center of the d6-e6 pawns, complemented by moving his a- and b-pawn one step forward and positioning his pieces on the 7th rank, Nf6 being the only exception.

When introduced by the young players of the 1970's, Ljubojevic, Andersson, Adorjan and many others, it served as the red cloth waved before the eyes of the old lion guard. To their great annoyance, even best of them, the likes of Taimanov, Polugaevsky and Uhlmann, could not bust the Hedgehog, instead, finding their own position in ruin.

Decades later, it is universally believed that White has no real advantage in the Hedgehog middlegame. Therefore, modern efforts are concentrated on acting fast right out of the gate to interfere with Black's setup.

Part 2 The Sveshnikov

The initial shock and disbelief of seeing Black ruin his position out of the opening moves has long worn off. Already for decades, the Sveshnikov has been accepted as a legitimate opening.

Today's efforts are mainly focused on what Kasparov calls a “Quiet Strategy” of 9.Nd5 Be7 10.Bxf6.

White neglects a chance to inflict further damage to Black's pawn structure by doubling his pawns on f6, and, instead, focuses on keeping control over the d5-square, while slowing down Black's counterplay with f7-f5. Kasparov devotes quite a bit of attention to this plan. He shows a lot of games, including his own against Lautier, Moscow Olympiad, 1994, where the idea of pushing the h-pawn forward was introduced.

Newer games I show in the video do not set new directions. White is trying to dig a little deeper looking to pose some practical problems. Caruana's plan with c2-c4 is one promising idea, although Black seems to hold his own.

Part 3 Be3 Najdorf

This deployment of the bishop is mainly associated with the English Attack plan of f2-f3 and g2-g4. Indeed, White has played it extensively against a variety of Black's setups to a great deal of success. One might say that the English Attack is solely responsible for the decline in popularity of the Sicilian Defense. Yet, the Najdorf keeps its circle of devotees, led by Anand, Grischuk, and Nepo. The theory there has extended deep into the middlegame, and that fact alone has become a problem.

In that respect, I find the game presented in the video interesting. Two young players from the United States cross their swords in a less explored territory, as White tries to combine Q-side castling with f2-f4. Tactics abound, so enjoy the ride!

Part 4 Black plays ...h5 in the Dragon

Kasparov is right, the ...h7-h5 idea has brought the Dragon back from the dead. Ten years after he shared his thoughts on that White is still looking for answers.

The Karjakin-Carlsen game shows White trying to go all the way, only to see his own position ruined. On contrast, Nepo attempted a much quieter strategy against the young Chinese star Wei Yi and failed miserably. Of course, White can try again, but the renewed interest in alternative plans is understandable. Nakamura won the principled battle against Robson in the 9.g4 line. Maybe, the truth can be found there.

Part 5 Classical Scheveningen

This line set the stage for a classic Game 24 battle in the second match between Karpov and Kasparov. Garry won that game and the World Championship Title with it, so the Scheveningen has a special place in his memory. How did this variation stand the test of time?

Honestly, it has all but been relegated to obscurity. Perhaps, the popularity of the English Attack, which is particularly effective against the black pawn on e6, is to blame.

Yet, I was able to find a handful of recent games that might interest the viewer. Particularly, I am fascinated with a fresh idea of playing the black queen to b8, shown in Zherebukh-Belous. I'm not sure how to get there in standard move order, not nonetheless, it is interesting.

Part 6 Neo-Scheveningen

Not sure I'm completely OK with the title Kasparov gives to this chapter. To me, Scheveningen without ...a7-a6 is rather old, as it was played in the 1960's and 70's by Korchnoi and then replaced by Kasparov's own Najdorf move order, designed to play ...e7-e6 later.

Garry choose that move order for the specific reason of avoiding the dreadful Keres Attack 6.g2-g4!

Myself, I had a tough time defending against it, while relying on 6...h6, which long has been Black's main reply.

Perhaps, it is time for a different approach. This video deals with a more resolute plan with 6...e5!?

Some kind of a Sveshnikov Delayed? Can Black make it work?

Part 7 In The Sicilian Labyrinths

Back to the Najdorf, and now it's 6.Bg5 turn. Big time theory from the 1970's onward, with contributions from the best players of the era: Fischer, Spassky, Tal and others.

After some 20 years of heavy theoretical research and lots of practical application, the consensus was reached that Black can hold his own in the Poisoned Pawn Variation. Garry brings us up to date with those lines, but in the last ten years or so there has been a renewed interest in the sharp e4-e5 push which was previously condemned by theory. Some efforts of Gashimov and Radjabov gained notoriety, and then Anand himself weighed in from both sides of the board.

Strangely, but it is now Black who's looking for improvements. One of them is to insert the move 7...h6, which may or may not be useful for a regular treatment of the Poisoned Pawn, but it also gives White an additional option of circling that bishop around to f2.

The biggest names in today's chess get involved in this, so stay sharp!

Part 8 Main Variation of the Grunfeld

Throughout his illustrious career, Garry Kasparov had often employed the Gruenfeld Defense as Black. Usually to a great success, although he had his share of problems in World Championship matches with Karpov and Kramnik. Perhaps, a bit exasperated, Garry once said that the Gruenfeld is OK as long as you remember the required ten exact replies in the ten lines your opposition can throw at you. Sounds like a chore, even to the best prepared player.

One of those lines is the Classical Main Variation with Be3, which I both faced numerous times and employed as White. In this video, I'd like to show some of my more recent experiences.

Part 9 The Hungarian Grunfeld

The Russian System of the Gruenfeld is characterized by the early Qb3 move, which practically forces Black to surrender the center. The black knight remains on f6, blocking Bg7, thus making the necessary advance c7-c5 more difficult to accomplish. The resulting positions have been debated for the past sixty years. The main line of ...Nfd7 is named after Smyslov, while Kasparov mainly employed the ...Na6 line in his battles against Karpov.

This video focuses on the third option, ...a6, known as the Hungarian Variation. Obviously, the right name as the efforts of Hungarian Grandmasters Barczay, Sax and Adorjan deserve to be recognized. All the same, in my days as a young master in Leningrad, a group of players headed by our local hero IM Mark Tseitlin, did a parallel research on that line. Basically, throughout my entire career, I only played the Hungarian against the Russian System. Some of the ideas I have tried were deviating from existing theory – see for yourself how good they were.

Part 10 Caro-Kann with 4...Bf5

The main line of the Caro has undergone a big transformation lately. Gone is the old Karpov defensive formation with the black king castling Q-side. Today's players prefer to castle short, leaving their hands free for active counterplay in the center.

Of course, having your king's castle compromised by the move h7-h6 is daring White to sacrifice and attack. One of the most successful examples of such attacks is analyzed in this video, although in my research I found lots of improvements over Black's play in that game.

Part 11 Caro-Kann with 3.e5

The Advanced Variation has grown to be into White's most dangerous weapon against the Caro. Of course, the Classical approach with Nf3 and Be2, championed by Nigel Short, remains the main line, but there's something to be said about the sharp alternative 4.h4.

In this video I analyze three different replies to it, each leading to extremely complicated positions that are on the cutting edge of modern theory.

Part 12 Sicilian with 2.c3

The two games presented in this video illustrate modern developments in the 2...d5 line. As Kasparov points out, in order to avoid a typical isolated pawn scenario Black would like to develop his LSB before playing e7-e6, but the departure of an important defender may cause him some problems with the b7-pawn and/or on the a4-e8 diagonal.

Once I decided to follow a Kasparov recommendation to play a sort of Botvinnik Semi-Slav reversed, where instead of trying to win back White's c5-pawn, I went forward with the e-pawn, soon getting it to come to f3, but, as the viewer can see, not a whole lot of good came out of it.

The second game showcases the new move 5...Bf5. The energetic play of MVL certainly poses a challenge to that idea.

Part 13 French with 3.e5

Kasparov gives his stamp of approval to the popular 6.a3 line, but in modern practice, Black sometimes try to anticipate it by changing the move order in favor of 5...Bd7, instead of the routine 5...Qb6.

It turns out he can use it to attack the white pawn chain from the front with ...f7-f6. While this idea contradicts the classic teachings of Nimzowitch that call for aiming at the base of a pawn chain, nevertheless I find it interesting.

Part 14 Zaitsev Variation of the Ruy Lopez

The Zaitsev was the battleground of the memorable Kasparov-Karpov encounters, but he doesn't get much of a spin these days. Perhaps, it's the Berlin to blame because in order to avoid it White is forced to put his pawn to d3 in the early going. Even so, when it comes to classical closed Ruy lines, most of the time it's the Breyer.

In the featured game, White preferred a more modest a-pawn advance on Move 12, instead of Kasparov's favorite 12.a4. It is interesting to see how Navara avoided the old recommendation 16.f4 in favor of 16.Nf3, previously played by Bologan, and how Morozevich's energetic play helped Black to wiggle out of trouble. Still, playing the Zaitsev remains problematic.

Part 15 Arkhangelsk Variation of the Ruy Lopez

In its modern interpretation, the Arkhangelsk is played without the early Bc8-b7. Maybe it shouldn't be called the Arkhangelsk then, and indeed I have seen the name Moeller variation attached to it.

Semantics aside, the biggest problem for Black lies in the highly developed lines where White's early a2-a4 forces him to sac the pawn b5. Possibly Black has enough compensation, as he certainly makes his share of draws in that line, but some players just don't care for that kind of play. For them, the alternative is to play 5...Bc5 immediately.

White, in his stead, can try to flip the script by retreating his bishop to c2 after Black pushes b7-b5 one move later. Then Black can follow the path paved by then Ukranian, and now already for many years, American GM Alexander Onischuk. Let's brush up on that.

Part 16 Metamorphoses of the Nimzo-Indian Defense

The Nimzo remains a top-shelf opening choice for the new generation of players thanks to it's richness of ideas. All sorts of different pawn structures may arise from, and one line that Kasparov left unmentioned (mostly due to space constraints, I believe) is 4.f3, which could take the game into a Benoni territory. Of course, it takes two to tango, and Black has other choices but 4...c5, but, still I find the resulting positions the most intriguing. The initial efforts to uphold White's colors were taken by Shirov, but lately it is also Mamedyarov who continues to push through.

In the featured game, Shakh was able to make the most out of his opportunities. Notice has been served to Black to get back to work.

Part 17 Queens Indian Defense with 4.a3

The Petrosian QID was where the young Garry Kasparov made his bones. His victories over Marjanovic, Ivkov, and Portisch, all starting with 7.e3 to get a mobile pawn center, and soon featuring the energetic breakthrough d4-d5, were simply magnificent. Yet, after suffering a setback in the first game of his match with Korchnoi, who cleverly employed a Gruenfeld setup with 7...g6!, Garry switched to playing 7.Qc2, and this is where theory developed for the next 30 years.

Lately, White has made an effort to return to 7.e3, preparing to meet Black's DSB fianchetto with a sharp thrust h2-h4. On this subject, I have a recent game to present.

Part 18 Queens Gambit Accepted with 3.e4

Every Russian Schoolboy learns the dangers of protecting his c4 with b7-b5 in the QGA. The black pawn chain comes under assault after White plays the inevitable a2-a4. Yet, there's an outrageous idea of sacrificing the exchange that already has been played by Nakamura and some others. Black models his play after some lines of the English Defense (1...b6), and , at very least, he has great proactical chances.

All this makes the featured game even more instructive. GM Atalik immediately returns the exchange and uses the time gained to support his pawn center and undermine the c4-pawn. Interesting.

Part 19 Semi-Slav Circle

Interesting title. Garry must be referring to the plight of White, who keeps running in circles trying to find a breach in what has universally been accepted as Black's most solid opening choice and has been adopted by the best players of our time.

The latest trend is to employ the Catalan setup, which basically means sacrificing the c4-pawn.

Alex Shabalov couldn't care less, he just wants to push e4-e5, bring his pieces to the K-side and checkmate Black. One of his more successful efforts is here, but in the notes, I list possible improvements for Black.

Nakamura and Mamedyrov advocate the b2-b3 plan to clear out some room for a Q-side pressure. It is more of a long-term concept, which, I'm sure, will be further tested in the future.

Part 20 Sergei Makarichev's Triptych

After ending his own playing career in mid-1990's Moscow GM Makarichev turned to different pursuits. Together with his wife, Marina, they became stars of their popular chess show on Russian TV. Little less is known about Sergei's coaching efforts, yet at one time of another, he was part of both Karpov's and Kasparov's teams.

In his contribution to this volume, Sergei talks about three different openings he extensively studied and played all the time. The unifying thought is in rejecting the traditional “White must play for a win” in 1.e4 e5 openings, as well as the transition away from his once beloved Richer-Rauser in favor of the Petroff Defense as a sharp opening for Black! In other words, reject the dogma and seek your own ways.

Well, the Classical Sicilian is all but dead now, while the Petroff is taking heavy fire, but Sergei's visionary thinking in the quiet Italian Game (or Ruy Lopez with d2-d3) structures is all the rage now. One out of three ain't that bad when you look 30 years into the future!

Part 21 The Chebanenko Legacy

The Moldovan master Vlacheslav Chebanenko was not known for his success as a player, but he left his legacy in his innovative research in the Slav Defense and the Rossolimo variation of the Sicilian.

The former is characterized by the move 4...a6, a seemingly pointless pawn push. Black, however, combines the threat of capturing the pawn on c4 with preparation for b7-b5. In the featured game, the Chinese star Ding Liren took the game out of the main line of Chebanenko's analysis by refusing to go after the bishop pair right away in favor of gaining space on the Q-side. His opponent, seven-time Russian Champion Peter Svidler, was able to liquidate the entire pawn mass from that side of the board, only to find himself under pressure from the white bishops.

Chebanenko's contribution to the theory of the 3.Bb5 Anti-Sicilian line was to introduce the immediate capture on c6, which leaves Black with a dilemma of how to recapture. The very recent game Caruana-Nakamura illustrates the modern approach to this problem. Hikaru captured toward the center and positioned his remaining knight to the edge of the board, not to interfere with his fianchettoed bishop and staying out of the way of his f-pawn. A fascinating concept.

Part 22 Volga Gambit

Known in the English-speaking chess world as the Benko Gambit, this opening is a strange bird. Contrary to most gambits Black's strategy is not to open up the center and go after the enemy king. Quite opposite, in fact. Instead, Black relies on his pawn chain e7-d6-c5 to provide him with sufficient space to operate on the a- and b-files, while welcoming near every trade.

Over the past few decades, White has tried pretty much everything to stem the tide of Black's play. The problem is, it takes his attention away from what he really needs to be doing, which is prepare e4-e5 and develop play against the black king.

The three games of my friend, Istanbul GM Suat Atalik, featured in this video illustrate a relatively new attempt to block Black's play by establishing an outpost for the knight on b5. Try, and it might work for you!

Part 23 Odds and Ends

Three different openings are covered in this video.

I start with introducing a particular line for White to combat the Modern Benoni, an attempt to interfere with Black's normal development by hitting the d6-pawn early and forcing the black bishop to an awkward square d7. Black's best remedy has to involve the typical pawn sac, b7-b5, but where and when?

Then I move on to a large concept of the hanging pawns Black willingly accepts in some lines of the g3 Queens Indian Defense. Those positions aren't easy to handle with Black, as he has to rely on tactical defense. Talented, then young at the onset of the 1980's, Soviet players, Leonid Yudasin of Leningrad and Lev Psakhis of Krasnoyarsk, were confident they could do just fine playing this style, and they did well against strong opposition of that day. Soon, however, some effective methods of combating this plan were introduced for White, and “order” was restored. Until now. In his preparation for the Candidates tournament in Moscow, the eventual winner of the tournament Sergey Karjakin, re-discovered those long-forgotten ideas and re-packaged them in the modern move order of Bb4+, then back to e7. Karjakin's success in the entire event was largely due to holding his own in this line.

The last game illustrates my own efforts to uphold another somewhat suspect line of the Queen's Indian, where Black keeps his bishop on b4 to recapture back with the c5-pawn, thus taking it away from the center. There are some pros and cons there, but, overall, this line seems playable for Black.

Part 24 Modern Reti - I

Back in the early 1980, I was able to elevate my game over the endless ranks of Soviet Masters (approximately Senior Master level of 2400+ here in the U.S.) to be able to qualify for later stages of the USSR Championship. This success was achieved through my work on the middlegame and, particularly, the endgame, at the expense of studying openings.

In 1981 I found myself playing against the likes of Dorfman, Sveshnikov and Timoschenko in the First League USSR Championship. All those big names had one thing in common: their defenses against my usual 1.d4 were sharp and well-analyzed. With no access to databases (personal computers were science fiction back then), I simply stood no chance against them in sharp lines of the Botvinnik Variation. Later the same year they met their match in Garry Kasparov, who scored some crushing wins with White, but at the time no one else know what to do!

So, I took my own path and ditched “principled” lines in favor of a home-brewed variation of the Reti Opening. Skeptical looks and disparaging comments aside, I persevered and kept on playing it. Watch my first experiences in this video.

Part 25 Modern Reti - II

The classical defense against the Reti is Lasker's ..Bf5, ...h6. I had no intention to follow the famous Reti-Lasker, New York 1924, as playing b2-b3 was never in my plans. Instead, White trades pawns on d5 early, to see how Black is going to recapture. In this video I concentrate on the structure appearing after ..exd5. White then plays his knight to d4, hitting the Lasker bishop and preparing e2-e4. The resulting positions are somewhat reminiscent of the Alekhine Defense with the colors reversed.

Lately, I hit a bit of a snag with this system, as the desired effect of the e-pawn advancing did not materialize in my games with Van Wely, and, particularly, Zherebukh. Back to the drawing board, I guess.

Part 26 Modern Reti - III

Back to the modern ...Bg4 reply against my pet system. A few problems recently appeared there.

a) What do if Black sticks to his Slav Defense program and takes back with the c-pawn? The resulting exchange Slav structure doesn't leave White with a whole lot of room to try for an advantage. I tried the e2-e4 push against Gausel and got a somewhat better endgame out of it. The later game with Hendrickson, however, was less encouraging.

b) In the ...exd5 variation Georg Meier demonstrated a pretty simple, yet, effective way of keeping control in the center by trading on f3 and pushing d5-d4. My attempts to counter this idea nearly amounted to a total disaster.

c) NYC's own Alex Lenderman developed his bishop to c5, ruling out my main plan with Nf3-d4. The game took a different route, transposing into a standard Queen's Gambit setup with the pawn minority attack as the main feature of play. I guess I can live with that.